International Climate Finance and Development Effectiveness:

Reflections on climate finance allocations and effective development cooperation

Adjunct Professor, Dalhousie University

Executive Director, AidWatch Canada

Draft, October 28, 2019

- A deepening climate crisis, particularly for poor and vulnerable people

The global climate crisis is accelerating rapidly with deepening and irreversible impacts on people, nature and ecosystems. In October 2018, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a landmark Report with a clarion call for transformative and unprecedented shifts in energy systems and use. Without deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions in the next decade (45% by 2030 over 2010 levels) the planet is likely to fail to live within the 2015 Paris Agreementpledge to keep temperature increases between 1.5oC and 2oC. The Report concludes “with very high confidence” that severe climate change and instability “will worsen existing poverty and exacerbate inequalities, especially for those disadvantaged by gender, age, race, class, caste, indigeneity and (dis)ability.” (p. 451)[1]

Already parts of the world have experienced severe climate impacts on food and water security, health conditions, livelihood loss, migration, and loss of species and habitat. At a 1.5oC increase, the IPCC Report estimates that 122 million additional people could experience extreme poverty, with substantial income losses for the poorest 20% in 92 countries, and with significant impacts on poor countries, regions, and places where poor people live and work. An increase of 450 million flood-prone people will be vulnerable to a doubling in flood frequency. Depending on development scenarios, between 62 and 457 million additionalpeople will be exposed to climate risks and vulnerability to poverty with a 2oC increase compared to 1.5oC.[2]

In June 2019, Philip Alston, the UN Special Rapporteur on Poverty and Human Rights, suggested that the climate crisis has multiple implications for the rights of poor and vulnerable people. “We risk a ‘climate apartheid’ scenario where the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger and conflict, while the rest of the world is left to suffer.”[3] He noted the profound inequality in which developing countries would bear an estimated 75% of the cost of the climate crisis, despite the fact that the poorest half of the world’s population, mainly residing in these countries, are responsible for just 10% of historical carbon emissions. He issued a worrying prognosis for the future of human rights:

“Democracy and the rule of law, as well as a wide range of civil and political rights are every bit at risk. … The risk of community discontent, of growing inequality, and even greater levels of deprivation among some groups, will likely stimulate nationalist, xenophobic, racist and other responses. Maintaining a balanced approach to civil and political rights will be extremely complex.”[4]

What will be the implications of large-scale global migration, which will be inevitable as the equatorial belt warms towards uninhabitability? How will this migration affect or strengthen already rising “authoritarian nationalist” forces. The climate crisis is a justice challenge of the first order.[5]

With a 1.5oC target being politically ambitious for most developed countries, the consequences of missing this target for vulnerable populations in the Global South will be profound. Five decades of development, the ambition of Agenda 2030and the achievement of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agreed by the international community in 2015, are seriously undermined without a strong political consensus in developed countries, focusing on renewed commitments to deeply transformativeaction on the climate crisis at the highest level.

How well is the international community addressing the profound implications of climate apartheid in its current commitments and allocations of international climate finance? Considering these challenges for human rights and a just global order, this paper examines 1) the current ambition in setting international climate finance goals; 2) the degree to which these goals have been met to date; 3) the trends in the allocation of this climate finance against Paris Agreementcommitments to give priority to vulnerable countries and peoples; and lastly, 4) the implications of good practice approaches in effective development cooperation for implementing climate finance through aid relationships.

- Setting international climate finance goals

In this context, all developed countries, including Canada, have an urgent obligation to heighten their ambition for climate commitments for the coming decade, at both the domestic and international levels. Governments at all levels must align public policies and actions towards transformed energy systems that reflect a commitment to the Paris 1.5oC target and establish a pathway to carbon neutrality by 2050.

In Copenhagen in 2009, at the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP15), the international community committed to US$100 billion in total annual international climate finance by 2020. This annual commitment was extended to 2025 at the 2015 Paris CSO21, which also adopted theParis Agreementon climate change.[6]

Yet, the imminent withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreementand the current structure for delivering international climate finance create significant challenges for the international community in responding with new ambitious international finance initiatives, particularly those that can give priority to those countries and people most vulnerable to the evolving climate crisis.

Aside from the overall target of US$100 billion, there are no individual or collective provider targets for their share of this target.[2] In 2016, the OECD and a number of DAC providers created a Roadmap(as mandated by Paris COP21) for achieving this US$100 billion target by 2020. Accordingly, developed country providers are expected by 2020 to contribute annually US$66.8 billion, of which US$37.3 billion is bilateral funds and US$29.5 billion is multilateral funds attributed to developed country providers.[7] The remaining US$33.2 billion (33%) is expected to be mobilized from the private sector.[8]

- Determining the levels of international climate finance commitments

In June 2019, the OECD reported that US$56.7 billion in public international climate finance was committed by developed countries in 2017, with an additional US$14.5 billion mobilized by these providers from the private sector. Overall, the OECD concludes that US$71.2 billion has been directed to the climate crisis in 2017 by developed countries against the goal of US$100 million in annual commitments by 2020.[9]

An analysis of this climate finance however is fraught with methodological issues, different practices in counting climate finance by different providers, and by the proliferation of different bilateral and multilateral channels for allocation of this finance. Of the US$56.7 billion identified above, US$27.0 billion was “bilateral public climate finance” derived from provider biennial reports to the UNFCCC and direct reporting to the OECD. This finance was allocated directly through providers’ institutions to partners in the Global South. The OECD (and most developed country providers) use the Rio Marker for climate to determine the levels of bilateral climate finance reported to the UNFCCC. But unfortunately the rules for determining bilateral climate finance are not agreed among all providers. In particular, providers report a bilateral project, where climate mitigation or adaptation is only one among several objectives of the project, to the UNFCCC at different shares of the project budget.[10]

US$27.5 billion in 2017 was reported as “multilateral public climate finance attributable to developed countries.” This finance is the result of providers’ core contributions to Multilateral Development Banks and allocations to specialized multilateral organizations and funds for climate mitigation and adaptation. But these amounts are also affected by technical differences between the methodology used by the OECD and the Multilateral Development Banks’ own determination of climate finance from their core resources.[11]

Credible developed country commitments for finance have been critical in sustaining trust in the UNFCCC political process on the part of developing countries, relating to the implementation of the Paris Agreement. The focus of COP24 in December 2018 was to achieve consensus on a “Paris Rulebook” for guiding its implementation. Among these rules were those intended to resolve and bring order and transparency to both the measurement and to the reporting to the UNFCCC of international climate finance.[12]

The negotiated compromise reached at COP24 revolved around greater transparency, specificity and detail on climate finance, with reporting mandatory for developed countries (and encouraged and voluntary for other countries). However, much is still left to the discretion of the reporting party, with a high degree of flexibility in determining what is climate finance and how to report it. What will be different after 2020 when the rules come into force is greater transparency in developed country UNFCCC reports on what they are reporting (what they consider to be international climate finance)[13]and how they are calculating their contributions. But there is still no agreed consistency in approach between reporting parties. When implemented in their 2020 reports to the UNFCCC, close scrutiny for assurance that all providers are reporting climate finance fairly and consistently will still be required. Developing country trust is likely to continue to be a significant issue in climate finance negotiations.

On the bilateral side, the OECD DAC Rio Marker is the main option for determining provider climate finance based on an assessment of the main objectives of each project. Since providers have different practices regarding Marker 1 (climate one objective among several), the credibility of the OECD’s total bilateral climate finance can be questions and it is difficult to compare providers’ relative efforts. Therefore budgets for Marker 1 projects have to be adjusted with a common approach across all providers. The approach taken in this paper is to include Marker 1 climate-related projects at 30% of their budget or disbursements.[3]While the level of this adjustment is arbitrary, it is the current practice of Canada and several other providers in their reports to the UNFCCC. It acknowledges the importance of mainstreaming climate concerns in projects, while also taking account the fact that these projects have different overall objectives and sectoral priorities.

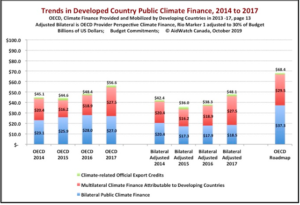

The results for an adjusted bilateral climate finance total are presented in Chart One. There isa noticeable difference in trends. The OECD data shows bilateral climate finance increasing from US$23.1 billion in 2014 to US$27.0 billion in 2017 (by 17%). Adjusted provider data, on the other hand, indicates a slight decrease in bilateral climate finance from US$20.4 billion in 2014 to US$18.5 billion in 2017, which is only half of the US$37.3 billion Roadmaptarget for 2020. Transparency on project details is relatively strong through the OECD DAC CRS dataset, which can permit an analysis of the allocation of this finance.

Chart One

Bilateral climate finance has been highly concentrated among a few providers. In 2017, these included:

France, responsible for 21% of total bilateral climate finance;

Germany, responsible for 20% of total bilateral climate finance;

Japan, responsible for 13% of total bilateral climate finance;

EU Institutions, responsible for 12% of total bilateral climate finance;

United States, responsible for 8% of total bilateral climate finance;

United Kingdom, responsible for 6% of total bilateral climate finance; and

Norway, responsible for 4% of total bilateral climate finance.

These six providers, plus the European Union, are responsible for 84% of all bilateral climate finance; their allocations set the overall priorities and approaches in bilateral climate finance. Canada’s share of bilateral climate finance in 2017 was 2%, alongside Italy, Sweden and Switzerland. But as a relatively modest provider of aid (10thin total volume of ODA commitments), Canada ranked ninth among twenty-four providers in climate finance.

As is apparent in Chart One, much of the growth in climate finance since 2014 has been through multilateral channels (which is even more pronounced if bilateral finance channelled through MDBs would also be considered). According to the OECD, multilateral financing has increased from US$20.4 billion in 2014 to US$27.5 billion in 2017 (by 35%). The Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), however, report their climate finance from their own resources (i.e. excluding bilateral funds managed through MDBs) at US$33.0 billion in 2017, with an increase of 28% since 2014. The difference is the OECD calculation of “attribution to developed country providers” from their core contributions.[14]While the MDB methodology for climate finance determines the particular share for each project where climate adaptation/mitigation is only one objective, there is little public transparency in accessing project details for those projects that each MDB includes as climate mitigation and/or adaptation.

The methodology deployed by the OECD for determining mobilized private sector climate finance has evolved in the past few years, making comparisons with earlier years not possible.[15] In 2017, the OECD determine that US$14.5 billion in private sector finance was mobilized through public finance instruments (such as Development Finance Institutions). The OECD collects data from bilateral and multilateral providers to make this calculation. This data is guided by a tangible causal attribution of the mobilized private finance for climate purposes to a public finance instrument. But the latter can include public finance loan and investment guarantees (accounting for more than 40% of blended financing overall), syndicated loans, buying shares in funds, direct investment, and credit lines. Again, there is no transparency at the level of project detail to verify the amounts and allocations of this finance (and in the case of the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, OECD officials themselves were only allowed to view data in an IFC secured room).[16] It is also important to note that guarantees are not actual expenditures, which only take place if the loan or investment defaults.

- Weak accountability for international climate finance

Systematic accountability in addressing the climate crisis has been very problematic over the past decade, both in terms of the allocation of international climate finance commitments and in relation to its potential effectiveness as a development resource. The remaining sections of the paper look at the development effectiveness of climate finance in two dimensions – a) allocation of finance for direct impact on vulnerable populations and countries; and b) consistence with principles that define effective development cooperation.

First, in terms of finance allocations, under the UNFCCC, developed countries prepare a biannual report on their greenhouse gas emissions and on international climate finance. As noted above the rules for inclusion of a project or flow are determined solely by the respective provider and not the UNFCCC.[17] There are therefore significant challenges in assessing provider performance in relation to reported climate finance flows.

Much of these climate resources, both bilateral and multilateral, have also been reported by providers to the OECD DAC as Official Development Cooperation (ODA). The OECD DAC publishes an annual report on climate finance, which is widely cited in climate finance negotiations at the annual UNFCCC Conference of the Parties.[18] While the DAC is careful in avoiding double counting, particularly in relation to multilateral finance, they too rely on provider reports to the UNFCCC in constructing their annual reports.

Compounding accountability challenges, climate finance has been allocated through many different channels, some of which are bilateral projects, others dedicated multilateral funds in existing institutions, and still others newly created multilateral vehicles, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF). Developing countries face an uncoordinated, project-based and often opaque international climate finance architecture, which is difficult to navigate and certainly a barrier to clear accountability in coherent international financing strategies for their climate priorities.

The Green Climate Fund has been launched and mandated by the UNFCCC to be its primary channel for climate finance. The GEF has a North / South governance structure for decision making, giving it legitimacy as a financing instrument. It is seen to be transparent in its operations. But resourcing the GEF has been fraught with difficulty, with both the United States and Australia withdrawing their pledges. Less than US$8 billion in pledges were honoured in its first iteration and a current replenishment is seeking a modest target of US$9.5 billion. While a crucial resource, it is not yet seen to be the pre-eminent climate-financing channel. Other multilateral and bilateral initiatives provide dedicated climate finance, but are much less transparent and often difficult to access. In this context, systematic provider accountability for their climate finance is very difficult, beyond broad financing trends.

Much more is required, particularly in relation to accountability to the most vulnerable people and countries, who will bear a high cost from the climate crisis in the coming decades, with limited capacities and resources to respond. A focus on their priorities is crucial for an approach to climate finance that is consistent with Agenda 2030 (and its commitment to leave no one behind), international human rights norms, and international climate justice (those responsible for the climate crisis should bear the burden). According to Philip Alston, the UN Special Rapporteur on Poverty and Human Rights.

“It is crucial that climate action is pursued in a way that respects human rights, protects people in poverty from negative impacts, and prevents more people from falling into poverty. This would include ensuring that vulnerable populations have access to protective infrastructure, technical and financial support, relocation options, training and employment support, land tenure, and access to food, water and sanitation, and healthcare. Women face particular challenges in the face of climate change.”[19]

It is then important to ask whether current allocations in climate finance are meeting these needs. As will be developed in the last section, this accountability may be more possible at the country level than globally through the UNFCCC.

- Climate finance allocations that address the needs of the most vulnerable

With existing challenges in data, transparency and consistency in rules on what constitutes climate finance for providers, there is limited options for analyzing the degree to which climate finance focuses on the needs of the most vulnerable countries and populations. However, several proxies can serve to indicate some trends in climate finance up to 2017.

These indicators include:

- The balance between adaptation and mitigation;

- A focus on Least Developed and Small Island Developing States (SIDSs);

- The role of loans and grants in climate finance;

- Gender equality objectives in climate finance commitments; and

- The impact of principal-purpose mitigation finance on providers’ ODA.

Vulnerable countries and peoples will require significant allocations of finance to adapt to climate impacts already build into current levels of atmospheric greenhouse gases. The Least Developed and SIDSs have the least capacity and resources to meet their climate change objectives and developing countries as a whole are challenged by increasing debt burdens. Strengthening women’s equality and empowering women as development actors will be an essential dimension of responses that are inclusive and just. Finally, the impact of climate finance taken from aid budgets is an important factor affecting the allocation of aid for other poverty-reduction purposes.

5.1 The balance between adaptation and mitigation

The Paris Agreementcalls for “the provision of scaled-up financial resources [which] should aim to achieve a balance between adaptation and mitigation, taking into account country-driven strategies, and the priorities and needs of developing country Parties, … considering the need for public and grant-based resources for adaptation.” [Article 9, 4]

The Global Commission on Adaptation, lead by former Secretary General Ban-ki-moon, Bill Gates and Kristalina Georgieva, CEO, World Bank, launched Adapt Now: A Global Call for Leadership on Climate Resiliencein September 2019, with an urgent call to ramp up adaptation finance.[20] The Commission notes the critical importance of addressing plausible and highly damaging and catastrophic scenarios (for example, increased drought and storms, deteriorating ocean environments affecting livelihoods, increase in the spread of diseases for which health systems are ill prepared). These impacts threaten the existence and livelihoods of many communities and societies. They draw attention to World Bank evidence that climate change could push 100 million more people below the extreme poverty line by 2030, with disproportionate impacts on women and girls. They call on providers to invest US$1.8 trillion in five key areas for adaptation by 2030.[21] An earlier estimate by the UN Environment Program put adaptation requirements at between US$140 and US$300 billion annually by 2030.[22]

What has been the experience in adaptation finance from providers since 2014? An estimated 27% of total climate finance (bilateral and multilateral) in 2017 (Chart Two), aims to support adaptation. Despite an overall increase from 22% in 2014, these resources are not close to achieving sufficient resources, nor a balance with mitigation.

Taking account bilateral climate finance and climate finance reported by MDBs from their own resources, adaptation climate finance commitments in 2017 reached approximately US$14 billion, far from the minimum US$140 estimated to be required, while mitigation commitments were US$37 billion.[23]

Chart Two

Chart Three

Bilateral providers have made some progress in giving priority to adaptation in their climate finance; however, the reliance on multilateral channels, and MDBs in particular, for most climate finance to date, is focused mainly on financing mitigation in middle-income countries in blended partnerships with private sector actors. (See Chart Three) Even the UNFCCC-mandated Green Climate Fund struggles to achieve an adaptation/mitigation balance. A review of 113 projects financed up to June 2019 (US$5.5 billion) reveals that only 38.6% of committed funds have been directed to adaptation.[24]

Clearly, much greater efforts are also needed in mitigation international finance to achieve the 1.5oCelsius Paris Agreement target (as well as making mitigation an urgent priority in provider countries themselves). But given the likely future impacts on climate already build into existing and expected greenhouse gas levels, current allocations for adaptation are woefully inadequate to create greater resilience in development approaches and adapt infrastructure, in order to protect vulnerable populations.

5.2 A focus on Least Developed and Small Island Developing States

The Paris Agreementcalls for developed countries to pay particular attention to “those that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change and have significant capacity constraints, such as the least developed countries and small island developing States, considering the need for public and grant-based resources for adaptation.” (Article 9, [4]) The degree to which current climate finance for adaptation addresses the needs of these countries is an indicator of provider coherence with this Paris commitment.

Chart Five

A review of bilateral and MDB climate finance shows that only 27% of adaptation finance has been directed to Least Developed, Low Income and Small Island Developing States (SIDSs) in 2017. This share has declined in recent years from a high of 34% in 2015. Bilateral finance performs somewhat better than MDB adaptation finance, with an average of 33% in the four years, 2014 to 2017, compared to 27% for MDBs (See Chart Five). The Green Climate Fund performed much better with LDCs and SIDSs receiving 50% of total GCF funds explicitly devoted to adaptation.[25]

5.3 The role of loans and grants in international climate finance

While the Paris Agreementstresses the importance of “grant-based resources for adaptation” (Article 9, para 4), the level of loans in the overall profile of climate finance is an ongoing concern. The IMF is paying increasing attention to the financial sustainability of debt in low-income countries and some middle-income countries. The wide-spread use of loans to the private sector in developing countries for climate projects may seriously exacerbate debt distress for many of these countries.[26] As a basic principle of climate justice, developing countries should not be responsible for paying developed countries (principal and interest on loans) for measures to adapt or mitigate the impacts of climate change, for which developed countries are largely responsible.

Chart 6

The overall use of loans has been declining modestly from 45% of climate finance in 2014 to 37% in 2015. (Chart 6) However, given the commitment in the Paris Declaration, a worrying trend is the increase in loans in 2017 for adaptation after seeing a decline from 28% in 2014 up to 2016. Three providers – France, Germany and Japan – account for almost all loans in climate finance, and these three are among the largest climate finance providers. Together they make up 94% of loans in 2017. Both France and Japan provided more than 80% of their finance to adaptation as loans, while Germany’s share was 21% of its adaptation finance.

5.4 Gender equality objectives in climate finance commitments

Mainstreaming gender equality in climate finance is a critical dimension that will ensure inclusive and potentially transformative impacts for both adaptation and mitigation. Women play crucial roles in the adoption of resilient agricultural practices for example. In relation to mitigation, current initiates tend to ignore small-scale projects supporting clean development mechanisms of greater benefit to women’s roles in the household, and women are often disproportionately affected by unintended consequences of large-scale energy infrastructure development, all crucial areas for mitigation efforts.

Currently, the only measure of gender equality objectives in development or climate projects is the OECD DAC’s Gender Equality Marker. This Marker identifies projects in which gender equality is the principal objective (Marker 2) and projects in which gender equality is one among several project objectives (Marker 1).

Projects where gender equality is the principal objective is a good indicator of the degree to which providers are serious about their policies relating to gender equality and women’s empowerment. Gender Equality Marker 1 has serious limitations in measurement and quality assurance.[27] Merely placing an objective for relating to gender equality within a project’s many objectives will not accomplish the mainstreaming of issues for vulnerable women and girls in responding to the climate crisis.

A recent CARE analysis of gender-transformative adaptation, based on case studies, concluded that such projects must carry out climate vulnerability analysis that addresses the power dynamics, priorities and preferences of women.[28]They must devote specific budget to activities that will drive gender transformation on the ground. In many cases they must be accompanied by actions that also address structural barriers to gender equality, such as land ownership, division of labour and roles of women in decision-making. Unfortunately there are no provider measures in place to assess such approaches or even verify the gender-mainstreaming Marker in climate finance projects.

There is insufficient data to assess gender equality and empowerment is total climate finance. But the OECD data on climate finance gross annual disbursements for climate finance projects provides a proxy for the degree to which these issue likely inform climate finance as a whole. In 2017, two-thirds of climate disbursements (US$8.9 billion in disbursements out of US$13.5 billion) had no gender equality objective. (Table One) A mere $400 million in project climate finance or 3% of total climate finance for that year had a focus on gender equality as a principal purpose of the project (irrespective of the mitigation or adaptation objectives). The remaining 33% of disbursements were for projects where there was at least one gender equality objective, and a disproportionate amount was concentrated among adaptation projects.

Table One: Climate Finance and DAC Gender Marker

DAC CRS Gross Disbursements, All DAC Providers, 2017

Significant purpose climate finance at 30% of Project Disbursements

| DAC Gender Marker

Billions of US$ |

Mitigation | Adaptation | Total Climate Disbursements |

| 0 (No gender objectives) | $7.0 (75% of mitigation) | $1.9 (46% of adaptation) | $8.9 (66% of total climate) |

| 1 (One gender objective among others) | $2.2 (23% of mitigation) | $2.0 (49% of adaptation) | $4.2 (31% of total climate) |

| 2 (Gender is principal purpose) | $0.2 (2% of mitigation) | $0.2 (5% of adaptation) | $0.4 (3% of total climate) |

A commitment to develop gender equality policies in relation to climate finance is required.[29]Applying these policies to understand success factors and respond with gender transformative climate adaptation and mitigation is an essential condition for climate finance addressing major vulnerabilities for women and girls in climate change impacts.

5.5 Impact of climate finance on providers’ ODA

At the Bali COP13 in 2007, developed countries assured developing countries that ramping up international climate finance would not affect ODA dedicated to other urgent purposes such as health, education or improved governance. In 2009, developed reaffirmed in the COP15 Copenhagen Accordto, “scaled-up, new and additional, predictable and adequate funding … to developing countries [emphasis added, §9].”[30]The Copenhagen Accordestablished the US$100 billion target for 2020.

But what constitutes “new and additional” climate finance? Almost all providers’ climate finance has been included in their ODA, as they are allowed to do so under OECD DAC ODA criteria if these resources are concessional and target developing countries. The 2015 Paris Agreementfurther confused the notion of new and additional by defining it as “a progression beyond previous efforts” [Annex, Article 9]. This approach allows providers to establish their own benchmarks for what constitutes “new and additional.” In practice almost all climate finance has been included and reported as ODA.

The original commitment that climate finance be new and additional to existing ODA has been a crucial concern for developing country parties, further eroding trust. From a climate justice point of view, developing countries should not be paying for the impacts of climate change they had little part in creating; from a development finance perspective, increased development cooperation for all development goals (meeting the ODA target of 0.7% of GNI) will be crucial if developing countries are to achieve the SDGs. The impact on providers’ ODA is therefore an important measure of the degree to which climate finance is responding to the needs of poor and vulnerable countries and populations.

Table Twoprovides an overview of the share of bilateral climate finance commitments in total bilateral commitments for select climate finance providers.

France, Germany and Norway are among the largest providers for climate finance (see Section 3 above) and this finance makes up more than 10% of their current bilateral commitments. In the case of France, nearly half of its bilateral aid commitments are directed to mitigation or adaptation, leaving only 54% for other urgent areas of development.

For DAC providers as a whole 11% of US$106 billion in total bilateral aid is devoted to climate finance on average over the years 2015 to 2017. This share is certain to grow as climate finance increases and ODA is flat-lined by illiberal politics in many provider countries, which is marginalizing ODA. Without a change in policy and approach by providers and the OECD DAC, as international climate finance increases in response to the urgency of the climate crisis, ODA and its availability for realizing the SDGs (addressing widespread poverty and leaving no one behind) will be seriously compromised.

Concern should be focused particularly on the use of existing ODA resources for mitigation, which is the largest share of climate finance. Adaptation may be more consistent with good development practice, strengthening resilience in many areas. While mitigation finance is a crucial ingredient to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement, failure of ODA to address SDGs in relation to widespread conditions of poverty, exclusion and vulnerability, particularly in states with fragile governance, will only exacerbate the impacts of climate change. The latter may affect the capacity of the international community itself to govern in a worsening climate crisis and lead to substantial demands for finance for “loss and damage” from developing countries.

Select Providers, Share of Bilateral Principal Purpose Climate Finance in Bilateral Commitments,

Average Share, 2015 to 2017

Source: OECD DAC Climate Finance, Provider Perspective, and OECD DAC1 ODA data

| Provider

(Three-year average, 2015 to 2017) |

Principal Purpose, Total Climate Finance, as Share of Bilateral Commitments | Principal Purpose, Mitigation Only, Share of Bilateral Commitments |

| France | 45.5% | 32.4% |

| Norway | 19.5% | 18.1% |

| Germany | 17.8% | 14.7% |

| Austria | 16.6% | 14.6% |

| Finland | 11.6% | 11.3% |

| Italy | 10.3% | 5.6% |

| Sweden | 6.9% | 3.4% |

| United Kingdom | 6.6% | 4.2% |

| Japan | 6.3% | 5.6% |

| Canada | 5.6% | 2.8% |

| EU Institutions | 5.5% | 2.2% |

| Belgium | 5.4% | 4.0% |

| United States | 3.0% | 1.7% |

| DAC Providers | 11.3% | 8.0% |

- Climate finance consistence with principles for effective development cooperation

The notion of development effectiveness has been evolving over the past decade.[32]At the same time, its implications for provider practices and development outcomes have been affected by a changing and more complex development finance landscape. Emerging cooperation modalities, such as South-South Development Cooperation (SSDC), global International NGOs (INGOs) or blended finance with the private sector, have become more prominent, deepening a debate on development effectiveness. Climate finance is now a critical dimension of this finance landscape. Developed country providers will be pressed to respond to the undeniable and urgent need for dramatically increased allocations of climate finance. But seemingly climate finance has yet to be analyzed in relation to broad lessons from efforts to improve effective development cooperation.[33]

Since 2001, providers and developing country partners have engaged in High Level Fora, which have established benchmarks for assessing the effectiveness of ODA in the context of development cooperation. All stakeholders made commitments to improve the effectiveness of aid and its development impact (2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the 2011 Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation).[34]

Since 2011, the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) has brought together providers, multilateral institutions, partner countries, CSOs, the private sector, parliamentarians and foundations as a unique platform to advance the effectiveness of development efforts by all actors. It aims to support country-level implementation of its internationally agreed development effectiveness principles, which also inform the United Nation’s framework for ODA in development finance (see the 2015 UN Financing for Development Conference Outcome Document). The principles that were agreed in Busan for effective development cooperation expand upon the earlier 2005 Paris Declaration concept of aid effectiveness.

The four Busan principles that were agreed should guide effective development cooperation are the result of decades of learning and reflection on the experience of aid and development:

- Ownership of development priorities by developing countries;

- Focus on results that have a lasting impact on eradicating poverty and reducing inequality, on sustainable development, aligned with the priorities of developing countries;

- Inclusive development partnerships, recognizing the different and complementary roles of all actors; and

- Transparency and accountability to each other.

It was agreed that these principles must be implemented in ways that deepen, extend and operationalize the democratic ownership of development policies and processes, consistent with agreed international commitments on human rights. [Busan Outcome Document, §11 and §12(a)]

The Busan principles provide a robust framework for assessing development stakeholders’ development cooperation. There is a substantial literature on the degree to which these principles have in fact been implemented or even taken into account by development actors in their aid practices: What are the major challenges and influences on provider practices, and how can development practice on the part of all stakeholders be strengthened accordingly?[35] But to date public debates on climate finance seem to have largely focused on expanding the amounts of finance committed and delivered, with little attention to the determinants of its effectiveness for transformative change that protects the interests of vulnerable populations.

In putting forward a framework for assessing climate finance drawing on the principles for effective development cooperation, this paper draws upon the third GPEDC’s 2018/19 biannual monitoring process (3MR). The GPEDC monitors the implementation of the four principles against ten indicators for effective development cooperation. It is an exercise that was lead by developing country partners in more than 80 countries.[36]

Since significant portions of climate finance are allocated as ODA, the results of this monitoring should apply extensively to climate finance. Without more explicit focus on climate finance practices, the analysis below can only be indicative of potential issues, highlighted in the outcomes of the GPEDC monitoring, which should be taken into account for further research.

6.1 Country ownership of climate finance priorities

Country ownership is a key principle for Agenda 2030, which affirms that each government “will set its own national targets guided by the global level of ambition” and that the “global targets should be incorporated into national planning, policies and strategies” [Transforming our world, §55].

The Paris Agreement[Article 4, para 2] is consistent with a national planning framework, requiring each Party to prepare, communicate and maintain successive Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that it intends to achieve in reducing greenhouse gases. Developed countries support “for developing country Parties (NDCs) will allow for higher ambition in their actions.” [Article 4, para 5]

Similarly, Article 7 of the Agreementcalls for international cooperation to support adaptation plans in developing countries that are “country-driven, gender-responsive, participatoryand a fully transparentapproach, taking into consideration vulnerable groups, communities and ecosystems, and should be based on and guided by the best available science and, as appropriate, traditional knowledge, knowledge of indigenous peoples and local knowledge systems, with a view to integrating adaptation into relevant socioeconomic and environmental policies and actions, where appropriate [emphasis added].” (Article 7, para 5)

Democratic country ownership is an essential basis for inclusive country ownership of development plans and strategies, which must include NDCs. The GPEDC monitoring framework looks not only at the degree to which providers align their aid to country development plans and strategies, but also at country-level processes for stakeholder inclusion in the determination, and therefore the legitimacy of country strategies, priorities and results frameworks to which providers are aligning. What were the results in GPEDC’s Third Monitoring Round (3MR) in 2018?

Of the hundreds of projects examined in partner countries by developing country focal points, only 57% of bilateral projects were seen to be aligned with country results frameworks (derived from country plans and strategies), down from 64% in 2016 (Part 2, pages 28-29).[37] The 2019 Progress Reportnotes an improvement in country level planning, which in some cases is more inclusive. But it also concludes, “more systematic and meaningful engagement of diverse stakeholders throughout the development processes is needed.” {Part I, page 36) While almost all Governments in the 3MR (77%) report consulting with CSOs in designing national development strategies, only a small number (17%) confirmed that they allowed CSOs to engage in a participatory process to shape the national development strategy.

CSOs consulted in the 3MR process also observed that various forms of multi-stakeholder processes exist for dialogue on development priorities. But many of these processes are highly compromised by a lack of institutionalized regularity and can be perfunctory mechanisms to endorse existing government priorities with limited CSO engagement. CSOs continue to rate broad government consultation practices, in terms of timeliness, transparent documentation, openness, and iterative processes, either as very poor or needing significant improvement.

The case of Kenya seems indicative: “Whereas some CSOs are sometimes meaningfully consulted, there is no unified process of consultative input, and thereafter implementation, monitoring and validation of the results of development efforts are similarly limited.”[38] Years of development experience suggests that transformative and sustainable development strategies “owned” across sectors, so essential for climate mitigation and adaptation focusing on transformation, but also for poverty reduction, will likely fail to galvanize support in the absence of meaningful inclusive processes of governance.

How aligned are providers climate finance allocations with developing country NDCs and stated needs for adaptation? There is little direct evidence, although it can be assumed that monitoring conclusions above on country alignment for bilateral aid broadly applies to bilateral climate finance. But within the climate finance architecture, the Green Climate Fund, with its direct participation of developing countries in its governance, and its reliance on proposals from developing country governments and other stakeholders, may validate a new approach that ensures greater country ownership of climate initiatives. The strong reliance on multilateral channels for climate finance in general allow for greater trends in these directions, with the very notable exceptions of provider-dominated MDBs.

The OECD is developing systematic reflections on the alignment of development cooperation with the Paris Agreement, most of which is not yet published.[39] A summary published in September however concludes,

“most providers have not defined what Paris alignment looks like. Climate strategies and mainstreaming approaches have yet to effectively enhance the consistency of development cooperation. Many providers also lack capacity to support transformative climate action in developing countries.”

This work includes the important dimension of policy coherence in provider alignment with the Paris Agreement. These issues of coherence are largely absent from the GPEDC’s approaches to effective development cooperation. The OECD observes that “the volumes of export credits reported for non-renewable energy production plants nearly quadrupled between 2010 and 2016, from US$12 billion to US$46 billion,” an amount that dwarfs provider bilateral support for climate finance during this period.[40]

Finally, a 2019 survey of 135 CSOs in 62 countries by Action for Sustainable Development on their experience with SDG follow-up and Voluntary National Review (VNR) processes, which would include actions relating to climate change, confirms significant limitations for inclusive policy making.[41] In the survey, 59% of respondents said that there was no opportunity (36%) or little opportunity (23%) to participate in an institutionalized ongoing review mechanism for SDG priorities in their country. A similar 60% had no or little opportunity to contribute independent evidence, assessments or reports based on their organization’s development experience.

At the same time, 66% had a modest to excellent opportunity as a CSO to work with other CSOs on these themes in larger groups or coalitions. Stakeholders are coalescing around these agendas, but face a frustrating absence of opportunity to engage governments (and multilateral institutions) and help shape legitimate plans and priorities going forward.

Governments are not only slow to enact their SDG commitments, but also 63% of civil society respondents in this survey noted “that there was ‘not a focus’ or ‘little focus’ (scores 1 or 2 on the 1-5 scale) on ‘those left behind’, and 65% of respondents saw ‘little’ or ‘no’ opportunity for such groups to engage at the national level.

CSO perceptions of the effectiveness of the Voluntary National Review (VNR) process at the country level (in both developed and developing countries) were also very mixed. In all measures of this effectiveness, more than 50% of CSO respondents’ assessments were “not effective” (level 1) or “marginally effective” (level 2). In 80% of the cases there was no funding for stakeholders to participate in official meetings (level 1) or very little funding (level 2).

In a comprehensive 2018 assessment of VNRs submitted to the annual UN High Level Political Forum to review progress in implementing Agenda 2030, on behalf of the Canadian Council for International Cooperation, “only a handful of VNR reports … included contributions from non-state actors and local governments throughout. VNR reports continue to remain silent on the enabling environment for civil society, and a limited number speak to others challenges that civil society organisations face in contributing to the 2030 Agenda.”[42]

Despite global commitments, only a minority of governments seem to be engaging civil society in the determination of SDG priorities and in their implementation, thus seriously undermining the chances for meeting provider commitments to align their development cooperation through inclusivecountry ownership. Such limitations will carry over to the essential task of building country consensus on societal priorities for climate mitigation and adaptation policies and plans.

6.2 Enabling CSOs for inclusive development partnerships

Given the scale of challenges arising from the climate crisis, sustained citizen engagement is a critical path towards de-carbonization, with ambitious goals for mitigation and adaptation across the globe. Recent mass mobilizations have taken the form of student strikes and massive citizens demonstrations uniting diverse constituencies in a deepening concern for the future of the planet, its people and biodiversity. Targeted resistance by indigenous nations and peoples alongside community-level environmental activists, organizing to call attention to particularly destructive projects, have had a long history.

Together, they are a vital force to increase political pressure for credible responses to the climate crisis – ones that begin to set genuine targets and take systemic actions to reduce greenhouse gases, while addressing massive needs for adaptation affecting the most vulnerable. They are demanding real accountability from politicians and corporations to these ends.

Yet, at the same time, Frontline Defenders, a human rights organization based in Ireland, confirms that 633 human rights defenders (HRDs) were killed in the most recent two-year period (2017 and 2018), mainly in developing countries. Of those killed, nearly three-quarters (72%) were “defenders working on land, indigenous peoples’ and environmental rights.”[43] Beyond killing HRDs, hundreds more environmental activists are designated “criminals” or “foreign agents” in both the Global North and South. They and their organizations continually face many forms of harassment and aggressive measures brought by government and corporations seeking to silence them. Women human rights defenders in general, but including those who are active on environmental rights and climate issues, face constant sexual harassment and abuse as well as continuous denigration women’s voices and issues.[44]

Open civic space, where people can freely organize and express their concerns and alternatives, is a crucial political foundation for inclusive development outcomes; it is a recognized condition for inclusive partnerships for SDGs through development cooperation. This space is particularly critical for civil society organizations (CSOs) that are seen to be politically challenging by existing power structures, whether in government or extractive corporations in minerals, oil and gas. These CSOs often represent poor communities, marginalized and repressed populations, bring together indigenous peoples’ voices and interests, or work to empower women and girls. Open civic space is a vital condition for innovative partnerships that can press for just solutions in the climate crisis, often contesting powerful interests rooted in a fossil fuel economy.

In recent years, attacks on civil society across the globe by governments and other powerful interests are growing and have taken many legal and extra-legal forms.[45] These conditions manifest differently in each country context, but are also increasingly generalized across a broad range of countries, with varying levels of democratic practice, in both the Global North and South.

According to the CIVICUS Monitor, a global CSO platform, a third of the population of developing countries (32%) live in 20 countries that are classified by CIVICUS as “closed” with no possibilities for independent civil society voices; a further 20% live in 29 countries where civil society is significantly “repressed” and 18% live in 43 countries where civil society is “obstructed” (civic space is highly contested by power holders).[46] Altogether more than 60% of the world’s population – 4.5 billion people – live in countries where civic space is closed, repressed or obstructed. Such conditions seriously undermine the capacities of civil society – and whole countries and societies – to advance Agenda 2030and the SDGs, including robust and just responses to the climate crisis.

Effective and inclusive partnerships are seen to be a core principle and approach in development cooperation, which aims to move from “whole-of-government” (i.e. exclusively inter-governmental partnerships) to a whole-of-society approach. Agenda 2030(and SDG 17 on the means of implementation) recognizes the importance of the complementary roles of different stakeholders, promoting such partnership across society in advancing the SDGs.

But conditions for inclusive partnerships that are effective in reach poor and vulnerable populations are not nearly a given for many civil society organizations. For CSOs, working through inclusive partnerships that are equitable and respect different societal interests, require all development actors to create an enabling policy and legal environment for CSOs. Civil society can reach vulnerable people and communities, bring context-specific development knowledge to the table, hold governments to account, defend the rights of vulnerable and marginalized populations, and support transformative change, all of which are crucial in raising government ambition in the climate crisis.

But evidence collected by the GPEDC’s 2018/19 country monitoring exercise largely confirms the experience of human rights organizations. The GPEDC’s 2019 Progress Report, summarizing observations by government, providers and CSOs, concluded, “constraints on civil society have increased, negatively affecting its ability to participate in and contribute to national development processes” (Part I, page 40). GPEDC reports from 82 countries are consistent with “the widely reported view that space for civil society is shrinking” (Part I, page 40).

This evidence suggests that opportunities for policy dialogue with government have increased in many of the GPEDC participating countries, yet most CSOs said that these are episodic and often perfunctory engagement on policies and priorities established by government. Unreasonable legal and regulatory measures affecting CSOs have become widespread across many countries, with restrictions on receiving external funding or regulatory harassment becoming more common practice.[47] As noted above, environmental activists and organizations have been increasingly targeted. Further research is needed to disaggregate and synthesize impacts of this civic environment for inclusion in adaptation climate initiatives or respect for affected communities’ prior, free, and informed consent in new mitigation infrastructure supported by providers through private sector partnerships.

Development cooperation providers can be playing a constructive role to strengthen enabling conditions for civil society actors, including through climate finance partnerships. But the GPEDC’s 3MR found major barriers for progress: 1) providers were not raising issues of CSO enabling conditions systematically in provider/government policy dialogue and projects; 2) providers consulted CSOs at the country level episodically, if at all; and 3) good practice in provider financial support for CSOs was weak, with very limited direct support to local CSOs in developing countries, and a move away from flexible programmatic CSO funding by some providers.[48]

More specific research is needed to understand better whether climate finance partnerships are strengthening capacities and roles for local actors, including civil society, to implement country NDC priorities, and hold their governments to account at all levels. The evidence suggests worrying trends, but also a lack of recognition of the challenges among climate actors and institutions. A recent example is a detailed guide for governments to strengthening national climate plans published by the World Resources Institute and UNDP. The Guide acknowledges the importance of planning for stakeholder engagement for “greatly strengthening the legitimacy, quality and durability of the NDC enhancement process,” but offers no advice on good practice, challenges, and measures to overcome barriers to participation by affected populations.[49]

6.3 Development partnerships and the private sector

Many bilateral and multilateral mitigation projects are carried out through public sector loans and guarantees with private sector finance in blended finance managed by Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). Providers argue that the use of public resources to catalyze this private sector finance is essential to make up the massive shortfall in capital (hundreds of billions of dollars annually) required to finance the transition to a non-carbon economy throughout the Global South. Recent research highlights issues in scale and purpose, but also transparency and accountability for blended finance, which are basic principles for effective development cooperation.

The OECD in its research has attempted to measure private sector finance mobilized by the public sector through blended finance.[50] Their best estimate is that a modest US$21.3 billion in private finance was mobilized for climate projects by public sector instruments (such as DFIs) in the four yearsbetween 2012 and 2015 (about US$5 billion a year). Of this amount, 87% was directed to mitigation and 13% to adaptation (dividing the 16% allocated to both purposes equally between the two). Almost half (41%) was in the form of guarantees (i.e. no actual public financial transaction), 27% in syndicated loans, 15% in special investment funds, 9% for credit lines, and 8% as direct investment. It seems that the expectations for the mobilization of significant private capital for SDGs by blended finance are unrealistic – on average blending institutions have mobilized only 75 cents in private sector finance for every dollar of public investment, which dropped to 37 cents for low-income countries.[51]

There are a number of critical issues in the expanding role of DFIs in development cooperation in general, which also apply to blended finance for climate mitigation and adaptation. Among these challenges are

- The question of whether private finance is truly additional because of the public contribution, or a public subsidy of an existing private sector initiative, which would take place without the public input;

- The need for much improved transparency at the transaction level;

- Demonstrated consistency with development effectiveness principles;

- The lack of impact analysis of development outcomes; and,

- An exacerbation of a debt crisis through increased loans in development cooperation (as noted above).

With respect to climate finance, these instruments have a very heavy bias towards mitigation purposes, and therefore a focus on middle-income countries, with a very weak track record on gender equality.

In responding to some of these challenges, all providers through the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) have agreed to a set of principles to guide the practices of DFIs. They adopted a set of very broad Blended Finance Principlesfor Unlocking Commercial Finance for the Sustainable Development Goalsin October 2017.[52] The OECD is currently developing guidelines for implementing these Principles. In parallel, some providers have supported the Tri Hita Karana Roadmap (October 2018), which sets out a shared value system (bringing together the DAC good practice and the DFIs principles) and identifies five key areas for action.[53]

The OECD Blended FinancePrinciplesare exceptionally general and largely uncritical of documented pitfalls for blended finance. They include 1) ensuring blended finance has a “development rationale”; 2) designing blended finance to increase mobilized commercial finance; 3) tailoring projects to local context; 4) focusing on “effective partnering”; and 5) monitoring blended finance for accountability and transparency. The Tri Hita Karana Roadmap, led by Indonesia and supported by several other providers, takes these Principlesand somewhat more firmly embeds them in shared values of development practice.[54]

Establishing broad principles to guide blended finance is an important first step. But creating a framework for assessing actual contributions of blended finance to development and the SDGs, including climate adaptation and mitigation, will be essential to their credibility. In this regard, at its July 2019 Senior Level Meeting, the GPEDC, with the participation of CSOs as full and equal stakeholders, endorsed the Kampala Principles on Effective Private Sector Engagement in Development Cooperation.[55] Bringing in key elements for effective development cooperation, the KampalaPrincipleswill serve as a framework for monitoring private sector engagement, including blended finance, through the GPEDC biannual country-led monitoring process.

The Kampala Principlesacknowledge “a number of challenges with private sector engagement [PSE] … [including] lack of safeguards on the use of public resources; insufficient attention to concrete results and outcomes (particularly for the benefit of those furthest behind); and limited transparency, accountability and evaluation of PSE projects [page 4].” Five principles are fully elaborated and provide normative guidance for assessing private sector engagement in development cooperation.

- Inclusive country ownership– Define provider/government national private sector engagement (PSE) strategies through inclusive processes, which should be aligned with national priorities and strategies;

- Results and targeted impact– Focus on maximizing sustainable development results while engaging in partnerships according to agreed international standards, including the International Labour Organisation labour standards, the United Nations Principles on Business and Human Rights, and the OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises.

- Inclusive partnerships– Support institutional inclusive dialogue on PSE and promote bottom-up innovative partnerships “in the spirit of leaving no one behind”.

- Transparency and accountability– Measure and disseminate results, towards remaining “accountable to the partners involved, beneficiary communities and citizens at large.”

- Leave no one behind– Targeting those furthest behind means recognizing, sharing and mitigating risks for all partners. Ensure that a private sector solution is the most appropriate way to reach those furthest behind. Carry out a joint assessmentof the potential risks for the beneficiaries of the partnership as part of due diligence.

Implementation of the Kampala Principlesby providers, DFIs and partner governments would bring a significant development effectiveness lens to blended finance projects, including those relating to mitigation. But the overall weak track record of providers over the past decade in carrying through reforms in their development practice based on the four GPEDC development effectiveness principles, unfortunately, does not give strong assurance that they will be seriously taken on board. Domestic political pressures in provider countries, and the reorientation of the MDBs to engage the private sector in filling financing gaps, may accentuate this marginalization of these Principles.

6.4 Transparency and accountability in development cooperation for climate commitments

Accountability to Nationally Determined Commitments at the level of the Paris Agreementis voluntary and weak. Mechanisms for reviewing compliance are non-binding and largely consultative.[56] The mechanism established in Article 15 is intended to be expert-based, non-adversarial and non-punitive, “taking account the national capabilities of Parties.” The word “accountability” does not appear in the text of the Paris Agreement. On the other hand, the December 2018 negotiated Paris Rulebook for implementing the Agreementadded substantial improvements in transparency (see section 3 above), while largely avoiding issues of accountability. Developed countries are now obliged to send more rigorous biennial reports, but there are no political forums in the context of the UNFCCC for discussing individual reports.

The UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance prepares an overarching and synthesizing biennial report.[57] These reports are based on national reports submitted by developed country Parties and bring attention to overall trends in patterns in finance (subject to the limitations of national reports).

Given the overall weaknesses of the multilateral system, including the UN and its bodies, for holding governments to account, the path to stronger accountability may lie at the country level.[58] The GPEDC stress the critical importance of partner-country led mutual accountability mechanisms in its framework for effective development cooperation.

Country level accountability mechanisms are an opportunity to hold providers (and partner country governments) to account for their financing commitments. They can also build incentives for behaviour change for all development actors, which is crucial to effective measures that respect country ownership in development cooperation. But meaningful country accountability requires country mechanisms that go beyond provider/government dialogues, with processes that are both transparent and inclusive of all development actors such as civil society, parliamentarians and the private sector.

The GPEDC’s Third Monitoring Round (3MR) was an opportunity to review the realities of mutual accountability in development cooperation at the country level. To what degree are there regular, institutionalized and inclusive mutual accountability dialogue on development cooperation priorities and finance? Are there country frameworks in place to guide these dialogues? Are there specific targets for the different development partners? To what extent are the results of accountability assessments transparent and accessible in a timely way to the public? These were the questions country level facilitators for the monitoring exercise asked in relation to current practices in their country?

The Progress Reportfound that quality mutual accountability mechanisms were seen by providers and government to be strong and improving in the poorest countries that rely heavily on ODA. But then among the 86 countries reviewed (many of which are middle income countries), fewer than half were found to have quality mechanisms. Most partner countries (86%) reported that they had targets for effective development cooperation with traditional bilateral and multilateral partners. But do various country stakeholders share them? How inclusive are these mechanisms?

Parallel data from the UN Development Cooperation Forum reported that a third of countries surveyed had no involvement of CSOs and another 20% reported minimal involvement. CSOs involved in the GPEDC 3MR concluded that mutual accountability mechanisms for most partner countries require significant attention to improving institutionalization, deeper and meaningful inclusion across a diversity of stakeholders, greater predictability, and full transparency in their documentation, deliberations and decisions for follow-up.[59]

Where mutual accountability mechanism exist and function with reasonable effectiveness, they present an opportunity for dedicated discussion of international climate finance in support of NDCs and adaptation needs. The latter, as noted above are substantially concessional ODA flows, which should already be included in aid targets and assessments at the country level. Unfortunately, as also noted, climate finance allocations are biased towards middle-income countries, where the GPEDC evidence suggests that few mutual accountability mechanisms exist at the country level. This gap in accountability is more complicated in these countries with a diversity and multiplicity of international financial relationships for climate mitigation and adaptation. But as this financing expands, partner governments and country stakeholders may benefit from strengthening dialogue at the country level with all development partners involved.

- Summary Conclusions

This paper began by asking how well is the international community addressing the profound implications of climate apartheid in its current commitments and allocations of international climate finance. It concludes with several summary observations drawn from the analysis:

- Ten years on from COP21 in Copenhagen, it is still very difficult to assess even the basics of international climate finance against the 2020 US$100 billion target.Clear provider accountability for this finance still lacks both a high profile common institutional space for a criticalexamination of reported finance as well as no agreed framework for assessing performance. Greater transparency in developed country reporting agreed at COP24 in December 2018 is undermined by a continued lack of agreement in the UNFCCC on what constitutes legitimate climate finance and on how different modalities of climate finance should be counted.

- Estimates of provider performance since 2014 are under-whelming.Bilateral climate finance in 2017 seem to be closer to US$20 billion than the OECD-reported US$27 billion; US$27.5 billion to US$33 billion in multilateral climate finance has been accelerating for disparate mitigation initiatives, particularly through the MDBs, but a reality check on MDB reporting is hampered by little accessible transparency at the project level; and mobilized private sector finance (said to approximateUS$14.5 billion) is largely self-reported by DFIs and is even less transparent. At best, by 2017, providers are likely allocating less than two-thirds (approximately US$60 billion) against the US$100 billion target. This finance remains highly concentrated in six major providers (France, Germany, Japan, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States).

- Climate justice requires attention and priority to the rights and interests of the most vulnerable people and countries.These six providers, along with the European Union and the MDBs, have shape climate finance allocations in ways that largely fail protect and promote their interests.

- Less than a third of climate finance (27%) is being allocated to adaptation for countries and people most exposed to the impacts of the climate crisis.Similarly allocations to Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States seem to be declining (at least for bilateral climate finance) and are affected by low levels of adaptation finance overall.

- With Germany, France and Japan being among the largest providers, loans to developing countries are a significant modality for delivering climate finance – countries and people, who have contributed the least to the crisis, are being asked to pay back developed country lenders for developing country efforts to mitigate further greenhouse gases and adapt to its major impacts on their livelihoods.

- Women and girls, particularly those living in vulnerable countries and conditions, receive no priority in climate finance – fully two thirds of bilateral climate finance project disbursements in 2017 had no gender equality objectives.

- Climate finance is an increasing proportion of ODA allocations, particularly for several strong climate finance providers – France, Norway, and Germany.Between 2014 and 2017 on average 11% of DAC ODA bilateral commitments has been devoted to climate finance. Increased climate finance is urgently required, but mitigation finance in particular should not be budgeted at the expense of ODA intended for poverty eradication. Efforts to reduce poverty, increased access to social services and support good governance are essential to success in tackling the climate crisis.

- Further research is needed to more fully elaborate the implications of good practice approaches in effective development cooperation for implementing climate finance through aid relationships.Democratic country ownership, enabling environments for inclusive partnerships, accountable private sector initiatives, and robust transparency and accountability at the country level are seen to be essential pillars for effective development cooperation, including climate finance.

- Preliminary evidence suggests that major challenges may limit the effective delivery of climate aid and its sustainable impact at the country level.

- The Paris Agreementcalls for country-driven, participatory and fully transparent approaches at the country level. The UNFCCC encourages countries to develop Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and adaptation plans; some providers have facilitated NDCs at the request of developing countries; and the Green Climate Fund responds to country proposals and includes developing countries in its core governance. Yet evidence from the GPEDC’s Third Monitoring Round (3MR) in 81 countries said that only 57% of major bilateral projects, which would include climate finance, were aligned with country results frameworks in 2018. Non-governmental stakeholders reported restricted and ineffective opportunities for engagement with government for the development and assessment of country development strategies.

- Political space for sustained citizen involvement in public life is an essential foundation for social inclusion in effective country climate action strategies.But the ability of citizens to hold governments to account and press for planet and people-friendly policies and initiatives is under serious attack in increasing numbers of countries. Governments harass and undermine the credibility of environmental and human rights organizations through unreasonable prosecution under CSO laws and regulations, with 60% of the world’s population estimated to be living in countries where civic space is closed, repressed or obstructed. In 2017 and 2018, at least 633 human rights defenders were murdered, with almost three quarters from indigenous, land rights and environmental rights backgrounds.

- The involvement of Development Finance Institutions in climate finance through blended initiatives, combining government public resources with private sector finance, has escalated in recent years, although total amounts seem still to be quite modest.Blended finance is an important modality for climate mitigation projects. Yet there has been little attention to whether public finance in these initiatives is little more than a subsidy to the private sector, whether projects can demonstrate consistency with development effectiveness principles, and whether increased loans in blended finance are exacerbating a growing debt sustainability problem in poor and middle income countries. The development of robust principles by providers at the OECD and at the GPEDC to guide these initiatives has yet to be tested in practice.

- Accountability in the climate finance architecture at the global level is weak.Inclusive country level accountability mechanisms for development cooperation may be an opportunity for various stakeholders to hold climate finance providers to account, but also a public incentive to change behaviour of actors to be more consistent with development effectiveness principles. According to the results of the 3MR, these accountability mechanisms have been improving in some countries that are highly dependent on aid, but unfortunately were weak in other country contexts with more complex financing flows. In more than half of the country mechanisms examined, CSOs reported no involvement or just minimal token participation.

As the global crisis accelerates, providers for climate finance have an obligation to step up the scale and effectiveness of financing for developing country partners to strengthen their capacities in energy transition and resilient adaptation. But they must do so by paying much greater attention to the needs, interests and priorities of the many vulnerable countries and populations that will bear the major impacts of climate change so far largely unchecked. Lesson from 15 years of discourse and country attention to conditions for effective development cooperation can provide a useful framework for sharpening this finance as a tool for inclusive and transformative change for millions of affected people.

[1]This paper is adapted from recent work by the author: The Reality of Canada’s International Climate Finance, 2019, a report prepared for the Canadian Coalition on Climate Change and Development (C4D), October 2919, accessible at www.aidwatchcanada.caand Civil Society Reflections on Progress in Achieving Development Effectiveness: Inclusion, accountability and transparency, a 2019 report prepared for the CSP Partnership for Effective Development (CPDE), June 2019, accessible at www.aidwatchcanada.ca. The author alone is responsible for the integration of findings from these reports into this paper.

[2]This paper uses the lexicon of “provider” for a donor in development cooperation, and “partner country” for a recipient at the country level in development cooperation, common to the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation.

[3]The paper adjusts bilateral climate finance by including all principal purpose climate finance (Marker 2) at 100% of budget, dividing equally between the two purposes the budget of projects where the purpose is both mitigation and adaptation, including Marker 1 at 30% of budget, and excluding projects as Marker 1, when Marker 2 is indicated for one or other of mitigation or adaptation (in which case the budget is included at 100%).

[1] IPCC, 2018. “Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty,” October 2018, accessed August 2019 at https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/.

[3] Philip Alston, “Climate change and poverty: Report of the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights”, A/HRC/41/39, June 25, 2019, page 14, accessed August 2019 athttps://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Poverty/A_HRC_41_39.pdf.

[5]See Tom Athanasiou, “Globalizing the Movement,” June 2019, accessed October 2019 at https://greattransition.org/gti-forum/climate-movement-whats-next.

[6]See the UNFCCC Paris Agreementat https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement.

[7]Multilateral banks (MDBs) also allocate climate finance from their own internal resources generated by investments and loan portfolios. The $100 billion Roadmap tracks only allocations by the MDBs that can be traced to a developed country provider core contributions to that MDB. The MDBs produce an annual Joint Report on all climate finance provided by the MDBs. The latest version of this Joint Report is accessible at https://publications.iadb.org/en/2018-joint-report-multilateral-development-banks-climate-finance.

[8]Roadmap to US$100 billion, 2016, Figure 1, page 8, accessed September 2017 at https://dfat.gov.au/international-relations/themes/climate-change/Documents/climate-finance-roadmap-to-us100-billion.pdf.